Few phrases have been uttered more frequently in the wake of May 7’s general election than ‘the Northern Powerhouse’, a package of devolution proposals intended to decentralise government towards cities from Westminster. At the time of writing, transport – and specifically rail – is at the forefront of the plans, having also been a central plank in various policy reports issued over several years by bodies such as IPPR North.

The role of rail in the Northern Powerhouse focuses less on transport user advantages and instead accentuates wider economic benefits, such as improved labour market connectivity and agglomeration gains identified in other large semi-integrated conurbations, such as Germany’s Ruhr Valley region and the Dutch Randstad. Such philosophy has led the previous and current governments to back plans to invest up to £15bn on enhanced rail links between northern cities, but in practice this had coalesced into various options for new or very extensively upgraded corridors between Manchester and Leeds. This has, in turn, predictably led to calls for a ‘Crossrail of the North’ to be prioritised ahead of other railway projects, notably the second phase of High Speed 2. Indeed, economists and business commentators now take the benefits of some form of ‘High Speed 3’ advancing while HS2 is gleefully cancelled as almost absolute truths.

The ubiquitous Christian Wolmar aside, few transport commentators are so quick to leap to this conclusion, and with good reason. First, there is the blunt reality that rail’s most established and commercially-viable market is serving London, which is the origin or destination for almost two-thirds of all passenger-journeys. The corollary of this market reality is that the economics of regional railways are much more fragile, since volumes are less and yields lower. This in no sense undermines the case for improving rail links in the regions, but it does mean that major infrastructure works which do not have a ‘baseload’ London market attached to them are going to be more delicate to deliver.

The hurdles facing HS3 can be put into context by the highly unusual bureaucratic intervention required to ensure the replacement of the much-maligned ‘Pacer’ railbuses could be included in the next Northern passenger rail franchise. A letter released by the Department for Transport lays bare just how little of the benefits of new trains can be captured by established transport business case methodology.

Which brings us back to wider economic benefits. These ‘WEBs’ form a relatively small part of the economic case for HS2, which would link London with Leeds, Manchester and points north in a 540 km network centred on Birmingham. The chronic shortage of paths (let us not be distracted by load factor, a capacity red herring) on our north-south main lines, and the comparable cost of vastly less effective incremental upgrading schemes have ensured HS2 has made it to the hybrid bill committee stage, for the first phase at least.

Some of these issues can help spur the HS3 idea too, but if we are serious about improving non-London connectivity then the merits of HS2’s second phase must not be so routinely overlooked. The most stark comparison is to assess connectivity in the triangle between Leeds, Birmingham and Manchester. Today, there a whopping eight trains per hour linking Leeds and Manchester taking three different routes. Of these, five are express services with a standard timing of around 50 min. Contrast this with the Birmingham – Leeds axis, where only one train typically operates each hour and the journey time is almost 2 h. HS2 would cut that journey in half and offer at least twice as many trains – not that you’d know that from any media outlet whatsoever, including HS2 Ltd’s own communications team.

More pertinently still, HS2 has a key role to play in fostering the Northern Powerhouse itself by connecting the Sheffield/Barnsley/Rotherham area (assuming a Meadowhall station) with Leeds and York, while connections to the East Coast Main Line at Colton pave the way for a reduction in Newcastle – Birmingham travel times of around an hour, again with improved frequencies. And DfT and rail industry groups have long suggested that electrification can enable HS2 to be plugged into the cross-country network too, with trains originating in Bristol or Cardiff and sharing the new railway between Birmingham and York. A link with the conventional network in the Washwood Heath area of Birmingham to enable this should be added to the ongoing legislation for HS2's first phase.

Us northerners should nevertheless take heart that the wider economic benefits of rail investment, which for HS2 have been so roundly castigated by some in the London commentariat, are after all strong enough on their own to justify some form of HS3. But it would be exceptionally myopic to pursue this bold agenda for cross-Pennine connectivity while at the same time ditching more pressing enhancements, which include electrification, East Coast Main Line works and, yes, the northern sections of HS2.

Friday 15 May 2015

Tuesday 24 February 2015

HS2: McNaughton outlines the released capacity win

|

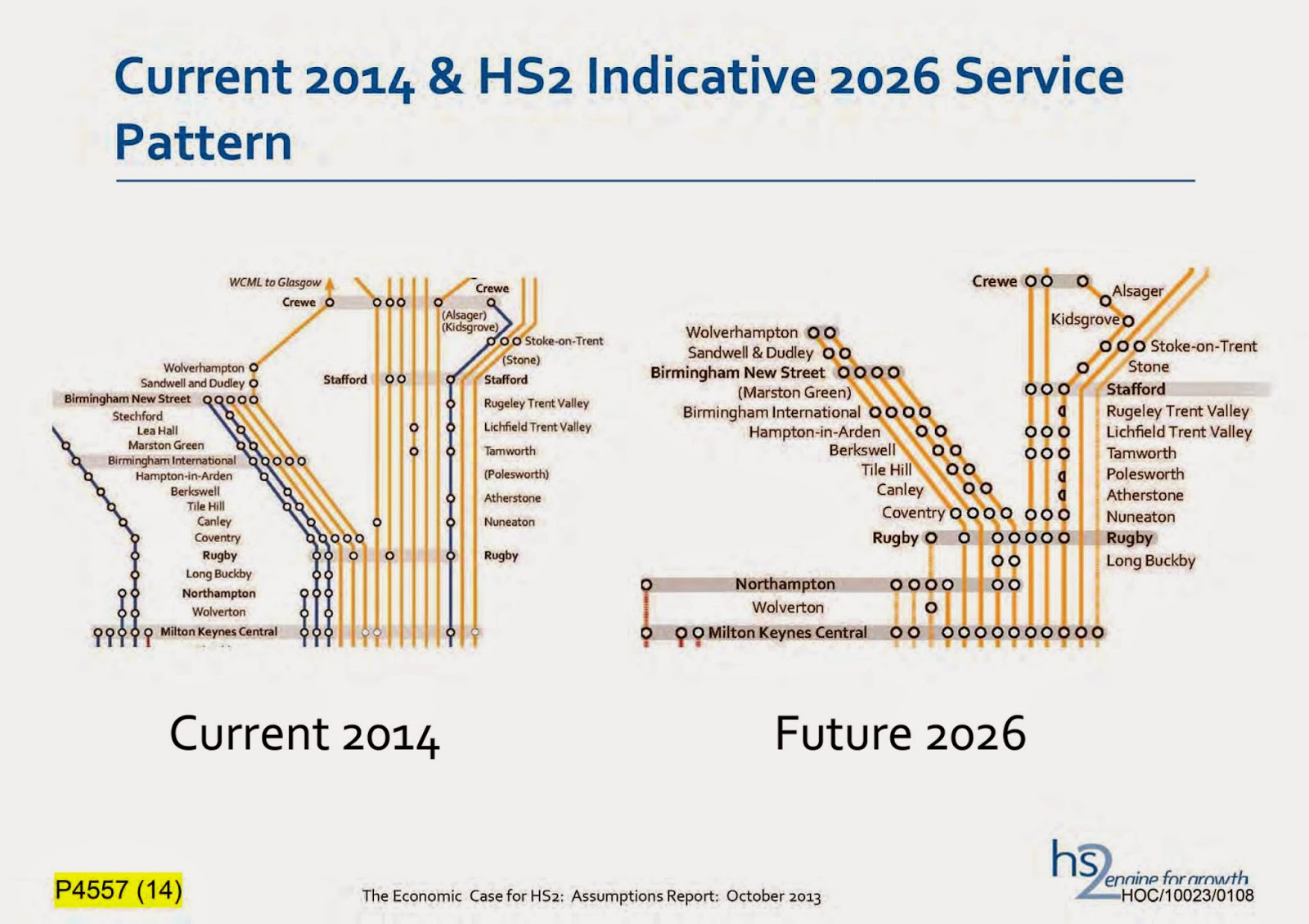

| Despite suggestions to the contrary by HS2 opponents, Prof McNaughton's slides made clear the increases in services which could be provided using capacity released by the first phase of the project. |

Professor Andrew McNaughton, Technical Director of the government's project delivery company HS2 Ltd, called it a ‘something of a canter’. But in reality, his appearance on February 11 before the committee of MPs scrutinising the first phase of the planned High Speed 2 railway network was a(nother) landmark moment, as it shone a light on one of the project’s most important assets.

In short, over these eight pages (pp41-49), McNaughton attempted to set out to MPs the nebulous, fraught and technocratic issue of ‘released capacity’. We hear it quoted so often as an advantage of HS2, but rarely do we see precisely how the hard bitten rail traveller – he or she with no inclination to board a long-distance train to London or Newcastle or Rotterdam or anywhere – might stand to benefit. And benefit a lot.

‘In each hour in the peak, because of HS2, there is the opportunity for the stations served by the West Coast Main Line to have around 6 000 to 7 000 extra seats. That is what released capacity equates to.’

McNaughton, not for the first time, sought to illustrate the issue by outlining, subtly yet effectively, how inefficiently our ‘patch and mend’ policies have led us to use our most strategic infrastructure, in the case the (notionally-upgraded) West Coast Main Line. In doing so, he drew a parallel with the country’s most capacious railway, London Underground’s Victoria Line.

‘If you recall, a few minutes ago, I said, in theory this is all non-stopping trains all going at the same speed, two minutes apart. You could end up with 30 trains an hour or, if they’re all stopping like the Victoria Line in the London Underground, 30 trains an hour. The practical limit on the WCML [fast tracks] today is 11 long-distance trains and four outer commuter trains, and there are trains on the slow lines as well. I’m going to concentrate on the fast lines. 11 plus 4 is 15.

'What does HS2 release? We take off the main line most of the long-distance non-stop services, because the purpose of HS2 is to serve cities on the long-distance network. That means in the peak we see at least 10 totally new services are available in the capacity that we released on the WCML.’

So, in a nutshell, we have a situation where we have a very old, but very expensively modernised, railway operating significantly below its theoretical capacity. That’s path occupancy of course, whereas much media brouhaha has focused on the question of seat occupancy or load factor. McNaughton addressed this too, noting that the provision of seating is a function of the number of train paths the railway is able to offer up. So needless to say, more seats might be occupied if more intermediate stops were inserted into long-distance trains on the WCML. Easy, right? Wrong:

‘The practical capacity is an operational capacity and this is not a fixed function for any particular railway; it is a function of how train services are planned on that infrastructure. I give some examples of how the way train services are planned affects the number of trains, the number of seats per hour, the number of stations, whatever, that can be served on a route.’

And the problem with the WCML – and the three other principal rail arteries HS2 would relieve in its second phase – is that, as McNaughton showed in his slides, it has to serve places en route, the ‘points A, B, C and D’ he cited. In commercial reality, B, C and D get a pretty raw deal: very few Virgin Trains expresses heading to or from London stop much south of Stoke, Crewe or Warrington. If they did, McNaughton reported, they would compromise the available paths for the two or even three trains behind. Then of course, any perceived load factor deficit would immediately evaporate.

As this blog pointed out recently, there is no longer any regular direct rail service between Watford and any destination in northwest England. A clear opportunity for the kind of inter-regional service which could (and in my view should) be offered in one of the 10 freed-up paths indicated by McNaughton.

It cannot be repeated enough that the fundamental usage of HS2 is already established. The services that will use it will in fact look remarkably familiar: faster and much, much more reliable, but still three fast trains from London to Birmingham and three fast trains to Manchester. The business case is a transferral and enhancement, not the dreaming up of a new market.

Indeed, of the 30 stations proposed to be served by HS2 trains once both phases are open, 21 are exactly the same stations as served by the equivalent services today (Warrington, Glasgow, York, Newcastle, London Euston and Manchester Piccadilly are among those in this group).

Unsurprisingly, and without reference to the slides that accompanied McNaughton’s presentation, those who remain dogmatically opposed to the HS2 programme leapt before looking. Others have highlighted the gross misrepresentation of Stop HS2’s description of McNaughton’s presentation, but such heat and light obscures the reality that our time-honoured patch and mend philosophy has led us to spend £10bn on a railway which afterwards defies efficient or reliable operation.

As we near the frenzy of a General Election campaign, primary evidence of a technically-credible nature is sure to be in short supply. Like Chris Gibb’s landmark report before it, McNaughton’s contribution is a vital one. HS2 can herald not just a highly-effective railway in its own right, but it can also unlock the potential of our legacy network. It must be built.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)